Review: Rosco DichroFilm

Paul Collison, and some blokes who should know better, take a new colour filter to places it should never go.

Review & Photos:/ Paul Collison

Dichroic gel. It sounds like an oxymoron. However, it’s not. Dichroic gels are here. Before we go on, though, it’s important to understand dichroics and how they work.

Dichroic colour filtering and standard gel filtering work in very different ways.

Standard lighting gel allows the specific wavelengths of the colour you want to pass through and out the other side. The unwanted light is absorbed by the pigment in the filter and released as heat. Standard modern-day gels are usually made on a polyester substrate, while the high temperature versions are generally made from polycarbonate. Life expectancy can depend on the saturation of colour and how the actual film has been treated over its lifetime.

On the other hand, dichroic filters use microscopically thin layers of metals to allow the desired colours of the spectrum to pass through, while reflecting the rest away from the filter. This method allows for a more pure light to be transmitted. In fact, dichroic filtering can allow up to around 90% light transmission as compared to 60% from standard gels. Ultimately this means we can get brighter colours, more saturation and an overall finer colour rendering from dichroic filtering. Dichroic filters can and do last many times longer than standard gel, so although there are higher costs involved for dichroics, they can pay dividends in the long run.

Of course there is always a catch.

MORE INFO

CONTACT

Rosco Australia: (02) 9906 6262 or [email protected]

NOT QUITE PERFECT

Light needs to pass through a dichroic filter at as close to a right angle as possible. Stray too far and you’ll start filtering out the wrong wavelengths and discolouration starts to appear. So using a dichroic filter on the end of a narrow optical system like a profile spot is usually okay. Put one in front of a fresnel spot and you may start to get colour problems at the outer edges of the beam. The other catch is that until now, dichroic filtering has only been achievable with the metal layers bonded on to a glass substrate. As we all know, glass is brittle at the best of times, so including sheets of dichroic glass in your touring lighting system has never really been a practical option. Until now.

Yes, the innovative brains at Rosco have come up with DichroFilm: a dichroic filter on a high temperature plastic substrate. All the benefits of dichroics, with the ease of use, and most importantly forgiveness, of traditional gel. At the moment DichroFilm is only available in 10 colours but one could safely assume that as demand for these filters increases, so would the range. Currently the range is only a handful of highly saturated colours, plus colour correction blue and orange.

One downside with dichroics is the confusing way they look. If you have a blue dichroic over a lamp, the blue wavelengths are the ones that pass through the filter. If you look at the film (as you would a piece of gel on the end of a par can), you actually see yellow – evidence of just how efficient these filters can be. So don’t go getting a rig full of dichroic filters for your 600-par can world tour. You might be a little surprised.

While not being the cheapest solution to gel at around $48 for a 150mm x 150mm cut, these new filters are now a viable option for touring musicals, long-running stage shows and the all important architectural market. You can be sure that Cirque Du Soleil’s accountant would love not having to change the thousands of cuts of gel for O at the Bellagio each week (not to mention the poor shmuck who has to change them). As our (not so) scientific field test establishes, these new filters are hard to break.

BOYS ON FILM

It was a humid couple of days in Rockhampton when the thespians of Queensland got together for their annual NARPACA (Northern Australian Regional Performing Arts Centres Association) conference. Your writer, along with some other more respected lighting professionals, got his hands on a cut of Rosco DichroFilm Hot Pink (Magenta 09476). Our small posse of inquisitive minds quickly decided to find the hottest, brightest fixture we could lay our hands on. Our gaze almost instantly found the Robert Juliat Victor follow spot. It’s bright; it’s hot inside; it was perfect. However, not content with dropping this lovely piece of new technology in its traditional safe place (far away down the end of the follow spot), we removed the iris control that was approximately 150mm away from the 1800W MSR lamp. This would be the perfect place for little Hot Pink. ‘Perfect’, as it would give us an idea of just how resistant to high temperatures the product is, and ‘perfect’, as we could focus the fixture on the actual material and see, without a microscope, just how the surface of the gel would react.

By now our posse had turned into a mob – one enterprising thespian began taking bets on the time before the gel would erupt into flames. Sadly (of course I mean, ‘fortunately’), the gel survived the first few minutes – unbelievable considering the ambient temperature in this part of the optical chain is around 300˚C. We discovered that the inconsistencies in the colour we saw were mainly due to oily hands that had inquisitively fondled the gel before it was installed. After the first 20 minutes, the oil had simply evaporated. The beam from our spot had a distinctive discoloration around the edges of the beam. It was concluded that this was due to its proximity to the source and, after some manipulation of the filter, was significantly reduced. Of course, had we put the gel down the cooler end of the spot where the colour is designed to go, this discoloration would not have appeared. It was apparent the ability to curve the gel would make these filters much more viable in wide-angle luminaires like fresnels and cyclorama lights.

After two hours, the mob had become thirsty for blood – they wanted to see something smolder. We decided to pull out the dichroic gel and inspect it for the first time. After two long hours just inches away from a blistering 1800W MSR the DichroFilm was in pristine condition.

This just wouldn’t do.

We grabbed some standard Lee 126 Mauve and 128 Bright Pink from the store in the Pillbeam Theatre – eager to placate those thirsty for smoke but also to see just how much this new filter differs from the old. First up was the 126. It’s hard to say just how long the filter lasted as the gel melted before it got all the way in the gate. This may have been due to the saturation of the 126 (according to an audio guy) so we tried the lighter 128. No go. Not even enough time to start the stopwatch before old 128 shrivelled quicker than a Bondi Iceberg.

We were all well impressed, but not entirely satisfied.

HAVEN’T THE FOGGIEST

We decided this test needed something to move things along. We had hit a plateau. Some fog fluid caught the eye of a certain un-named Australian representative of an un-named New Zealand-based luminaire manufacturer. We figured that it would not be out of the question for a technician to refill a fogger and then quickly change a gel before being able to wash his hands [yeah, right – Ed].

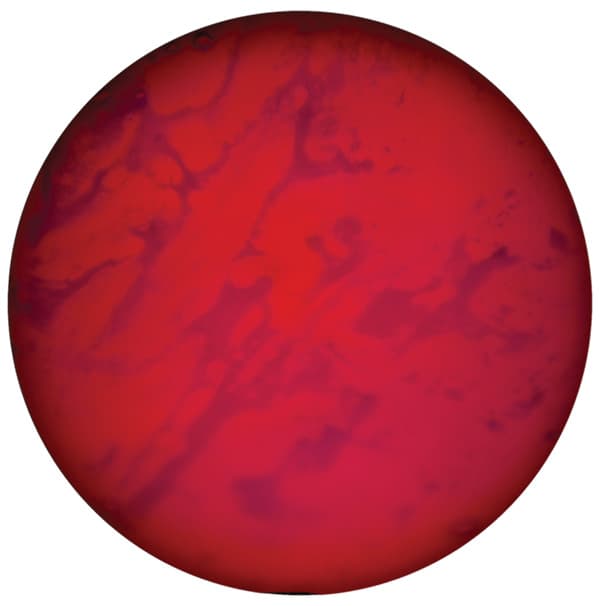

We washed the filter down with some fog juice and some more oily hands before dropping it back into the Victor follow spot. Instantly we could see the difference. The water in the fog fluid evaporated pretty quickly and we were left with a congealed mess on our beloved dichroic gel. Urgent action was required. We rushed the DichroFilm from the spot on to the nearest chair for some emergency first aid. We tried to wash it down with water and then inadvertently scratched away some of the metallic dichroic coating from the substrate. Surely now this would be the catalyst for the filter to degrade quickly? Alas, no. In fact, it was a rather cool look – similar to a Solar250 with a broken rotator (for those old enough to know what one is). We could clearly see where the integrity of the filter had been breached (due to being able to focus too clearly on the actual film) and we all assured one another that this was where the filter would start to self-destruct. It never did.

Five hours we waited for the filter to shrivel up and die but it wouldn’t. Soaring temperatures in the gate of the follow spot all but annihilated the standard gels in less than a second but the DichroFilm survived over five hours. By this time we had noticed some discolouration and inconsistencies in the gel, however these more than likely could be attributed more to the fog fluid and water than anything else.

Exhausted, the mob dispersed, defeated by a small piece of Hot Pink.

RESPONSES